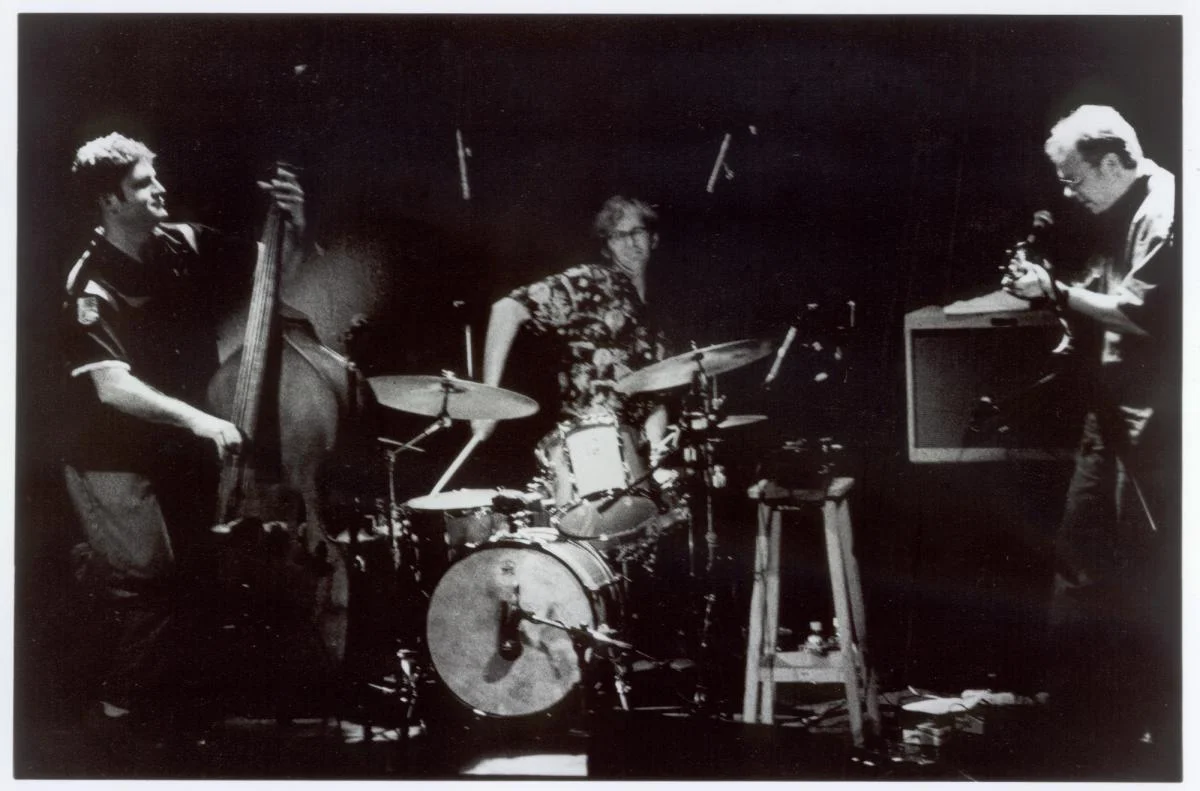

Photo credit: Michael Wilson

"The first time I saw Jimi Hendrix was after his first record came out. I heard it and it was so shocking, I mean, I loved it but I couldn’t … it was so much more than the guitar. Like the sound of his voice and the guitar together in that way, it was like this … I don’t know how to describe it. It was just so large or something. It was too much to comprehend as just being guitar."

LR: We’re talking with guitarists that we love, getting their stories and their relationship to the guitar and how it developed, music and technique and their inspirations and trying to tell the story of the guitar through the last century and into this century and pose the question of where it’s going and you know, just thinking about that via the stories about the power of the guitar, musically, culturally, these ideas. The first question about your own personal history of the guitar, how you came to the guitar, your story of the guitar …

BF: When I really think about it, it’s my whole life. Some of my earliest memories … I was really fired up about it. I was born in 1951 and one of my vivid memories when I was really young was my father bringing home our first television set … it had to be 1954 or1955 or something like that so I’m like 4 or 5 years old and I used to watch the Mickey Mouse Club on TV… I’ve told this story a million times before. Actually it even goes before that. I don’t have a memory of this but I found a picture of me and my grandfather and I had to be either 2 or 3 years old and I was holding a ukulele, like pretending I was playing the ukulele and he was holding this little miniature fiddle thing… whatever that was, I don’t even remember but that was way back there. I think it’s so much to do with America. You know I grew up in kind of a Leave It to Beaver, Father Knows Best time … you know, we had a house in Denver and I watched TV all the time and went to school and rode my bike but what was happening was, on that Mickey Mouse Club, at the end of the show, you know, it’s all these kids and there was the older guy, Jimmy, who would get his guitar out and they’d gather around and they’d sing a song together. I was so fascinated by just the look of it, well, you know he had a guitar with Mickey Mouse painted on the front of it. But there was something about the way it brought everybody together. There were all these adventures, this would happen and that would happen and then at the end, everyone calmed down and gathered around and the guitar it was sort of like a magic wand or something, you know. That’s something I started thinking about much much later. I didn’t know what it was at the time but I think just the object got me fired up. And even that far back I took a piece of cardboard and cut it out to look like a guitar and put rubber bands on it and I was pretending like I was playing guitar. And you know, a couple years go by and I get a transistor radio. I remember that was another just huge moment, like getting that transistor radio and I was just listening to the radio all the time. I was into hot rods and I wanted to be a race car driver and then the stuff with surfing started happening the first actual record I bought with my own money was a Beach Boys single with Little Deuce Coup on one side and Surfer Girl on the other side and then I would be looking at record covers with all those surf bands, like wow, the guitars were all mixed in with the cool hot rods and … the way people’s imagination was going, it was like cartoons and all mixed with the hot rod thing was the artists that drew this amazing like Big Ed Daddy Roth and like the car designers and fender guitars and I grew up with that and it seemed like it wasn’t all that unusual to be into it.

LR: Right.

BF: Yeah, Everybody was excited about it. It wasn’t like I was off by myself

LR: It wasn’t even counter cultural.

BF: Yeah. You’re a kid and one day you are playing sports and the next day you get a guitar and …

LR: Like girls and surfing and cars and guitars ..

BF: Yeah, but it was also, I was super shy and I was too scared to ask a girl out or to dance or anything and somehow then the guitar started to become more of a … it was my way of somehow being social.

LR: Right.

BF – I couldn’t talk but I could play and the music quickly became this … I guess I haven’t analyzed this completely but there was a point when it did become more like I went down in the basement by myself, hiding out, playing by myself … but I wasn’t playing by myself either. No, that was my social world, finding other people to play with.

LR: So at that time were you guys playing surf rock and some of this stuff?

BF: It was the summer of 1965 when I got my first electric guitar so you know, it was a little bit after the Beatles had been on the Ed Sullivan show and it was like instant. Like I think I had a gig like about a week after I got my guitar. (laughter) My friend down the block got a guitar and I had one and there was a guy that played drums across the street so we played for a party. We could play like 3 songs or something. It just seemed like immediately as soon as you even had the instrument, you know, we would just play for parties in someone’s basement and eventually we started playing for a dance at the school. But it seemed like it happened kind of quick …

LR: Yeah right, there was a need. That’s cool. So how did it progress from surf rock and rock culture and then I mean obviously at some point you got deeply into the instrument and jazz and at some point you studied clarinet, so how did it transition from rock to the other stuff.

BF: Yeah, that kinds of blows my mind when I think how fast things were coming at me, coming at everybody. I guess I was at that age where I could absorb things quickly, like a young teenager but when I think about how I was so quickly being exposed to new things but also how quickly things were evolving. Like think about how the Beatles’ music changed in 3 or 4 years. But at the same time I would hear that and it was like peeling the layers off of an onion or something. Like I would hear the Beatles and at the time I didn’t even know oh, that’s a Chuck Berry song or that’s a Buck Owens song they were playing. But immediately I would hear the Rolling Stones and all those British bands were playing blues stuff. Manfred Mann, I loved that band and they were playing Muddy Waters songs and I didn’t know who that was. I just thought they were playing music, like who is Muddy Waters? I’m talking about just within just a few years going from hearing Frankie Valli and the 4 Seasons, to the Beach Boys to the Beatles to the Rolling Stones to Paul Butterfield to Buddy Guy to Jr. Wells to Wes Montgomery to Miles Davis to Ornette Coleman in a period of 4 years. And it’s crazy now when I think about it. Like just from my years from 7th grade to 12th grade, it all happened within those 5 years.

S- And at the time, like Hendrix, what he was doing with guitar, was that something you were aware of? Like were you going ‘Oh my god this guy’s doing something totally radical.’

BF: Oh yeah … The first time I saw him was after his first record came out. I heard it and it was so shocking, I mean, I loved it but I couldn’t … it was so much more than the guitar. Like the sound of his voice and the guitar together in that way, it was like this … I don’t know how to describe it. It was just so large or something. It was too much to comprehend as just being guitar. It was a sound, I mean, even now when I hear him, after all the years I’ve been playing … there were certain things he did where it almost overwhelms, there’s some kind of power that overwhelms everything and you can’t pick it apart or analyze it. Just an incredible power. I saw him play twice. The only time I went to the Fillmore East, at that time my parents had moved from Denver to New Jersey and I went to see Blood, Sweat and Tears and it was late in December of 1969 and the Allman Brothers opened for Blood Sweat and Tears and at that point they didn’t even have a record and I remember like wow, I couldn’t believe the sound. You can get this book about the Fillmore East that has all these photos by this woman, Rothschild I think, and there’s this picture of the marquee and it says “New Year’s Eve, Jimi Hendrix, Band of Gypsies, December 28th and 29th, Blood Sweat and Tears” and I thought “Ahhh Fuck”, I mean I was thinkin’ I already saw Jimi Hendrix twice and I don’t need to see him. I was only inches away from …

LR: Oh yeah, one day away …

BF: Yeah, from seeing that, when they made that record, you know?

LR: Yeah that was amazing. My high school English teacher was there. I was always picking his brain about it.

BF – Really? But so much music I heard in those few years. Right after high school my parents left Denver and then that was when I, you know, I didn’t live in NY but that’s when I would come and first went to the Village Vanguard and tons of music was happening in Denver too. There was a place called The Family Dog and it was the same guy who did the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, was like the Joshua Light Show, sort of like the Fillmore kind of place in Denver. All the bands that played at the Fillmore and Avalon Ballroom would play there in Denver too and I heard Canned Heat and Big Brother and the Holding Company and Chuck Berry and Sons of Champlin and Blue Cheer and I don’t remember who all I heard and it was like a club, you know. I heard Buffalo Springfield.

LR: So at that time were you playing rock and roll or where you sort of transitioning into other things?

BF: Well by that time I had heard Paul Butterfield and Mike Bloomfield and I was like trying to play blues stuff. I was really into blues and kinda R&B stuff too like at my school, the band I played in, it was called The Soul Merchants, one of the bands, and we played all kinds of James Brown stuff and Temptations and to me, it all fit. I just hated the way things were split up that way. To me it was all blues. And then I heard a record of Wes Montgomery and that was a huge kind of gigantic revelation. It sort of was the link between all the pop music I’d been hearing and that’s what led me into discovering Miles and Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane and all that stuff.

LR: Well I guess when I think about guitar in some ways I feel like there’s a jazz approach on the guitar or maybe even more so than jazz, I guess like Mick Goodrick’s book comes to mind, like a non idiomatic very open-ended way of looking at the guitar, and you know, the guitar has 6 middle Cs on it and just the way that there’s so many possibilities of doing so many things on the guitar, like sort of the open -ended nature of the guitar. And then on this other side this very like idiomatic American guitar language

BF: Oh yeah,

LR: Whether it’s blues or country or all these rock and roll … I feel like for me your playing has always sort of explored the meeting grounds between those two things, the more open-ended jazz approach and trying to blend that with the sort of idiomatic American approach. I was hoping you could talk about that a little bit.

BF: There was a point when the instrument, for me, I really started thinking about it, like wow I just have this thing in my hand and there’s just no limit to what it can be.

LR: When would you say that was? Was it when you were younger?

BF: Well, jazz music helped me to start thinking more outside of the instrument itself when I really started listening to other instruments and it then just kept going from there. You know when you start listening to saxophone players and trumpet players and piano players and that just kept expanding when I was listening to orchestra or any kind of sound and being inspired by that and then thinking that the guitar was my way of channeling whatever was in my imagination in relation to whatever it was. But it was kind of gradual, just being open. I mean there were definitely times when, in the beginning I was just thinking about the guitar itself and then I was thinking about the guitar more in a larger context, like trying to copy Jim Hall or copy Wes Montgomery or John McLaughlin. I guess the more I learned the instrument I sort of …well, I’m still just trying to copy stuff but it’s more like a wider picture or something.

LR: Yeah … Via guitar, that makes a lot of sense to me. It seems like jazz guitar’s approach in so many ways, guitar is sort of later in the game in a way. It seems like you’re referencing piano and you’re referencing voice or saxophone or trumpet or whatever and then the logical next step from that would be ‘what about these world instruments, what about these folk instruments…’?

BF: Yeah, or just any kind of sound. But at the same time I think more and more I’m fascinated with … well, I hear some old, and when you talk about the future and when I hear like Son House or something, I think, god, how could it possibly be weirder than that?

LR: Yeah. Primitive technology is pretty advanced.

BF: I think more and more I hear idiomatic guitar or I’ll listen to a Bob Dylan record I used to listen to 50 years ago and I hear what he’s playing on the guitar and it blows my mind and it sounds incredible and I mean I can’t explain what it is but for me to actually execute what that is, I become fascinated with it and I’ll never get that right, you know. It’s endless. You know you look back and the more I understand what was happening before, the more my mind is blown by that. It’s incredible to think of what something must have sounded like. Like imagine hearing what Robert Johnson sounded like when you just walked into someplace and you saw this guy sitting there doing that. That would be the most outrageous radical thing that you’d ever heard in your life and like trying to imagine what was that and how do you make that happen now … like I think about it being something so extremely avant garde and weird back then but at the same time it was like the most beautiful thing that was so obviously anyone could understand it on an emotional level, like you were suddenly seeing the most beautiful thing or hearing the most beautiful thing you’ve ever heard in your life but at the same time it’s brand new, you know, it’s like you’ve just dropped in on another planet and somehow that has something to do with … I mean, I think somewhere in your question you said something about going into the future, I mean it’s all imaginary and impossible and that’s some of the stuff I think about. How could you ever do something like that and it would be new but everyone would get it.

LR: Right, totally .. Well, so my next question is about the emotional side of guitar. There’s a great video on You Tube that I watch sometimes which is Santana giving a lesson on how to play Europa and he talks about the outer technique and the inner technique and he has this idea that the inner technique is sort of the emotional technique of playing the song. You know, I really love your playing and obviously there’s a conceptual and a technical side to your playing and you really have a direct connection to the emotional side of your playing and obviously there’s just the human side of that and the artistic side of having emotions and feelings but I’m curious about if you thought about or how you approach the emotional side of guitar.

BF: I don’t even know if it’s something that’s conscious, I mean that’s what just takes over, that’s where I wanna be. I mean, I work on trying to get myself together technically on the instrument, I mean I’ve spent my whole life doing that but that’s not what I want to be doing. I mean when I play I’m not thinking about that. I just start to play and that’s what my voice is. Hopefully I’m not thinking about that stuff. Occasionally I’ll do some sort of workshop at a college or something and I almost feel guilty. I know it’s important to practice and try to improve and to learn all this stuff but sometimes that can get in the way. You know, if I spend all day thinking about some sort of mathematical pattern on the instrument which is great, you know, that’s all great, but if I go that night and I’m with my friends or I’m with the band and I’m gonna play some music, if I’m thinking about that, that’s not what I should be thinking about, you know, I should just be listening to what’s going on around me and sometimes by practicing a lot, that sort of gets in the way.

LR: Do you think the emotional side of the playing is like a different side of intelligence, maybe what you’re hearing, like the body or mind’s reaction to sound in real time with the playing, like it has its own kind of sense of intelligence or something?

BF: Yeah, I think when you’re really in the music, it’s indescribable, it’s this other thing that goes way beyond. You know, you can stop me and I can tell you what note I’m playing …

LR: You’re aware of that …

BF: But I’m not aware of it, not at all, when it’s really right. I can’t describe it, but I feel like that’s when I’m really myself.

LR: Do you think like speaking of the future of music, that’s like, for lack of a better word call it flow, or when musicians are sharing that experience, do you think that it has some sort of bridge to time or like all music is sort of connected in some sort of stream.

BF: Wow, I think it is. I don’t know if this is what you’re talking about but, you know, I’m almost 64 and you know, people have died now … more and more musicians I have heard and known and they have died and that’s really hard but I keep noticing things, like how the music is passed around. It’s unbelievable the way the music travels amongst us. It’s somehow incredibly comforting in a way. I mean you lose people but then I get these moments … like one time I was in the Village Vanguard and I heard Kurt Rosenwinkel play and it’s great and I’m kind of hanging out in the back. And I’m talking about like these 3 seconds of music and there was something like Wes Montgomery was in those 3 seconds and I was thinking wow, if Wes Montgomery was here right now I bet he would’ve really liked that. It’s like he was there or something in this weird way. It’s amazing how this stuff is transferred around without us consciously knowing it.

LR: I think that makes sense in terms of thinking about where the guitar’s going too, that there is a stream of ideas and they sort of evolve with people’s help and on their own. There are different trajectories that the humans are involved with and that they’re not involved with.

BF: Yeah, yeah for sure. And you know there’s always stuff with business, or CDs or whatever the record companies this and that … you know you can get all dark about, like well there’s nowhere to play or I’m getting ripped off by the record company

LR: Right.

BF: …but no matter what happens I feel like the music is strong enough that it always comes through, it’s always there. It might not be in the forefront, there are different times when it gets support but the music doesn’t have anything to do with any corporate evil empire thing or whatever, the music is always gonna be there. (laughter)

LR: (laughter) Yeah, I always think that the record industry has only been around for a hundred years but music’s been around for tens of thousands of years.

BF: Yeah (laughter), I mean some of it’s discouraging like wow, is everybody just gonna be playing laptops but no, there’s always somebody doing something cool somewhere.

LR: Yeah, totally. Okay, well my last question then is about your last record. You know I talked to Wayne Kramer from MC5 on Friday and he was saying he heard Rebel Rouser on the juke box when he was a kid and he’s like ‘what’s that thing? That’s what I want to do’, that’s why his mom got him a guitar at Sears because of Rebel Rouser, which is on your … Is Guitar in the Space Age your most recent record?

BF: Yeah …

LR: We sort of touched on this before but I’ve been really fascinated with that music too in terms of the guitar language of early rock and roll but it seemed really interesting to me you called it Guitar in the Space Age because obviously the 50s were the space age in a way and sort of the future and guitar was so futuristic and you are revisiting those things again now so I was wondering what your thoughts were in terms of the space age then and then the space age obviously eludes to the future now and sort of the relationship between that old guitar music and the future guitar, moving both directions.

BF: I think I sort of talked about that earlier, just talking about where and when I grew up and also how fast the stuff was going by, right? So part of the motivation to do that record was that I felt like I had just zoomed through all that stuff so fast from the time I started playing till I was on to whatever else it’s like wow, there’s no way I could have absorbed in that amount of time so a lot of it was sort of this research project for my own self. I wanted to go back and just feel what it feels like to play, like most of the stuff on that record is super obvious, you know, Rebel Rouser and Surfer Girl. I wasn’t looking for the most obscure stuff …

LR: The mainstream …

BF: Yeah, just to check it out and to strengthen where I’m coming from and at the same time I know it looks like a blatant obvious, like everyone says nostalgia this or nostalgia that and I guess that has something to do with it but for me it’s more about trying to learn where I’m coming from and also I’m looking at it like, it’s kind of a far out thing to enter into that stuff now after having played for 50 years. You know, you’re looking through this lens of everything else that’s happened and hearing it again and it just has this automatic sort of without even thinking about it, it puts this sort of weird filter on the lens or something. To me that’s pretty interesting.

LR: So as a research project, like playing those on the guitar, was there anything that came out of it?

BF: Well yeah, like right away I thought oh my god, I don’t even know how to play Pipeline or some of those surf songs and I didn’t spend that much time ever playing them. They’re hard you know …

LR: We read this fascinating interview with Dick Dale where he was talking about the rhythms you know from Miserlou. He was copying the snare drums of Buddy Rich or Gene Krupa…

BF: Yeah, yeah totally.

LR: These cool drum patterns …

BF: Yeah, you find all kinds of stuff. I say that a lot, the whole thing about higher and lower, like folk music is simple and classical music is hard and this one is easy and there’s no such thing as easy or hard. There’s no such thing. It’s all hard and you know to say Segovia is a better guitar player than Robert Johnson, you know, I’d like to hear Segovia play a Robert Johnson song.(laughter) You know it’s just absurd to even think that way.