It’s an honour to release this recording you made, almost exactly thirty years after it was recorded. The importance of the San people and the Kalahari desert, as being the cradle of humanity, as being the peoples that have both preserved the oldest gene pool surviving today as well preserving some of the world’s oldest traditions as well, makes this a pretty exciting recording to listen to. And then of course, imagining you there, with vintage gear in hand, 30 years ago, back when you had to travel with all your money in your sock, and travel based on trust, seems like a pretty intriguing picture. We were hoping you could give us some of the context for the record…

What initially prompted the trip?

I was in the Middle East and I met another English guy. He had a copy of a cassette with recordings of singers from Botswana on it and he was enthusing about it to such a degree that I got totally hooked. I wrote to a few contacts in Southern Africa and, to cut a long story short, I ended up with a Toyota pick-up, a Sony TCD5 Field Recording Cassette machine, two Crown PZM 30GPG mics and another friend from England, driving 9000 miles around nine countries in Southern Africa, recording 14 hours of rural music.

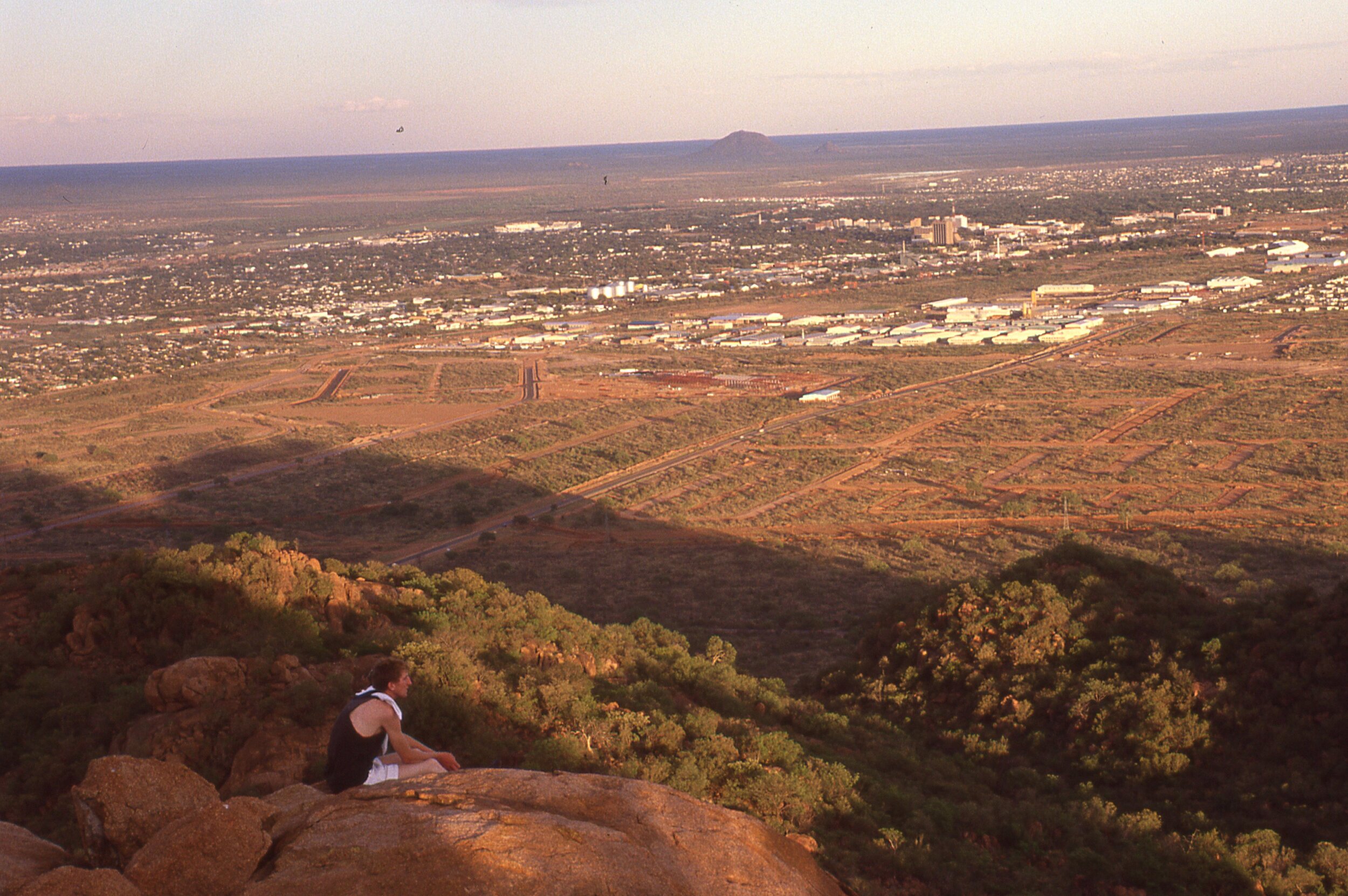

BUT that wasn't the trip when I recorded in the Kalahari!. Because of that previous experience, I got invited to return to Botswana to help organise a pan-African music festival. So I went back the next year and for five months was based in the capital city of Botswana, Gaborone. It was during this time that I made two separate trips deep into the Kalahari to visit and record the San.

Can you paint the picture of where you were in Botswana?

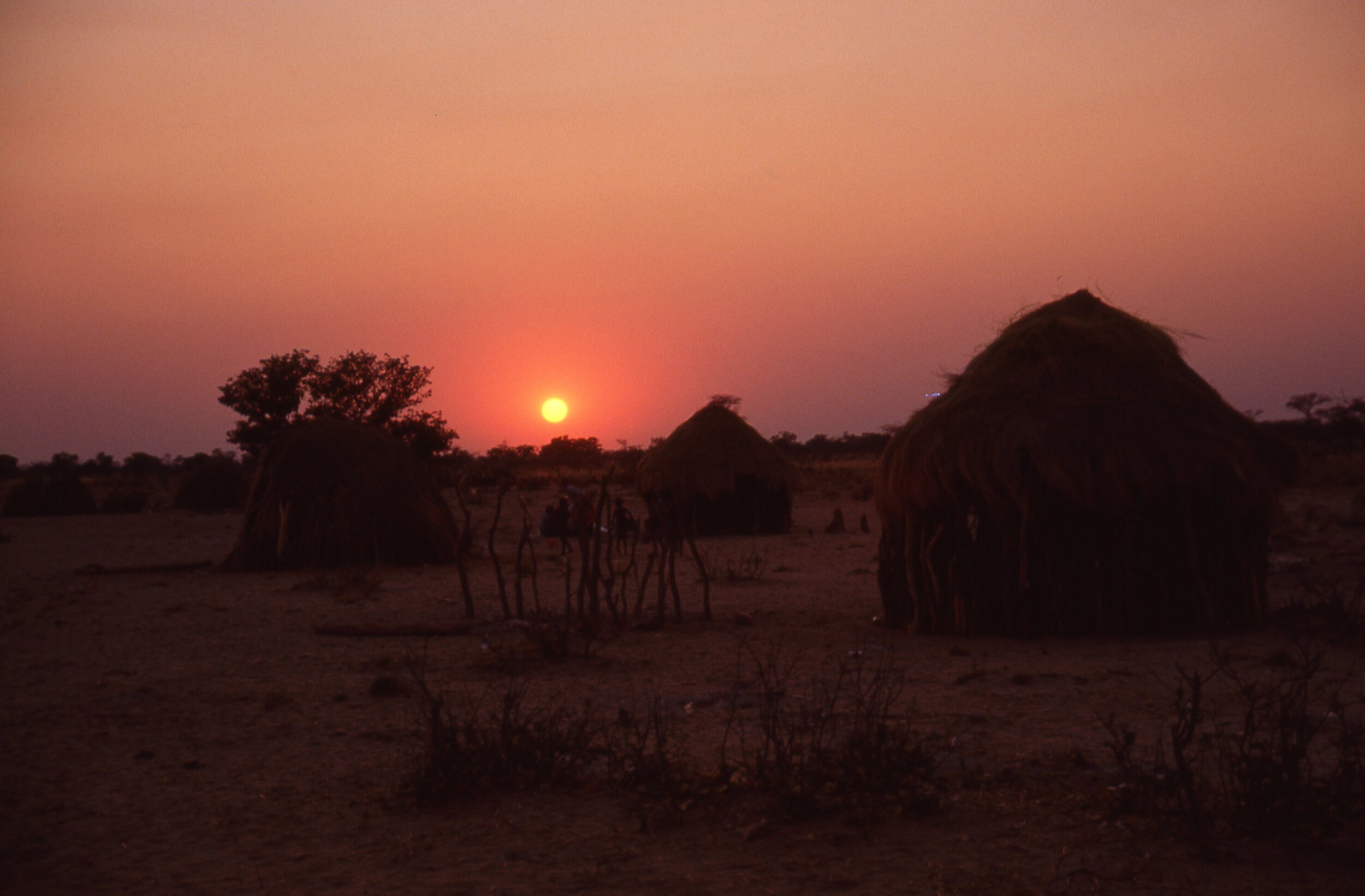

It took at least two, maybe three, days to drive there. Almost all sand road. I remember arriving at one settlement that was just a village of mud huts with straw roofs and so on. We were told this was the last major settlement before we went into the unpopulated part of the Kalahari. We had to stock up on water and provisions in that spot.

The Kalahari desert is exquisitely beautiful, it was spring too so although the bush colours were mostly tan and light greens there were the most colourful, sweet aromas coming off all the blossoms. Heavenly scents.

The Galalabadimo settlement was literally just a few shelters made of sticks and grass only. No mud walls. Someone went to clean the sand floor of a hut we were to sleep in and he came out with a huge white snake. Thanks. The nearest well was around a 40 minute walk through the desert, it was impossible to drive there. The water was extremely salinated, salty. Hard to drink, but it was the only water source. We had to walk back all that way with the heavy water containers. They had to do this every day or so of their lives.

The San are hunter-gatherers. Still are I guess. And often nomadic. Galalabadimo was a living arrangement somewhere between nomadic and tiny make-shift village.

You were recording at night? How did the recording come to exist? How did you meet and communicate with the folks you were recording?

I had some friends in the capital city, Gaborone, who knew of this Galalabadimo settlement and were connected to people there. On both trips there was someone with me that spoke Setswana (the national language of Botswana) and English. Some of the San spoke Setswana, but not all of them. They have their own languages Khoe, Kx'a and Tuu.

The vocal relationships in the Galalabadimo musics are pretty evocative - could you get a sense of themes, expression, or greater senses of communication?

I was diligent in documenting all the songs I recorded on my first trip around Southern African villages, but when it came to the San it was difficult, partly because of the three languages involved to translate stuff and partly because once they got going it was a real trance session, one song flowed into another and it went on for hours. I didn't want to stop them and get details. I'm sending this compilation to the !Kwhwa ttu San Culture and Education Centre (khwattu.org) so hopefully they'll be able to identify the songs.

We noticed most of the Galalabadimo songs on the record are in a count of 3 (3/4) or maybe 6 (6/4). Did you pick up any specific concepts on their rhythmic interplay between the claps, snaps and vocal lines of the Galalabadimo songs? Any notes of how the vocal parts were organised among the singers?

Do you know how composed/improvised the music is?

Any other thing in particular you’d like to point out in the music or any particular musicological things to note?

Did you get any perspective on their take on the music they were performing? Or their take on music in general?

I'm fascinated by the vocal music and can listen to it endlessly but I never went in and dissected it. I'm thinking that any music like this that has been performed for hundreds of years, likely longer, is just absorbed by successive generations, maybe not even taught, just learnt, like eating, walking or talking. It appears to me to have a lot in common with ancient musical forms I've heard in Mongolia and North America,. Definitely one thing they have in common is a deep connection and reliance on the natural world. I'm sure the music reflects that in a significant way.

It's interesting though how poly-rhythmic the San music is at the same time as being vocally polyphonic. That makes it sound really complex, it's difficult to decipher to what extent there are strict patterns in the vocal phrases and clapping and foot stomping.

The only thing I picked up at the time is that they would occasionally start bickering or teasing each other during or after a song. I didn't get a translation but it seemed like they were telling each other off for screwing up or singing the wrong tune or something. Like any band rehearsal anywhere. That suggests that total free improvisation is not necessarily part of it.

Were there any interesting stories you’d like to share? Any new cosmologies you came into contact with?

One thing that I remember as significant towards the end of my second trip to Galalabadimo was that having spent time with these folks and having recorded their campfire singing sessions and having felt an inspiring, human and musical connection with them, we heard the approach of vehicles. Half a dozen state-of-the-art Toyota jeeps pulled up. It was a package safari group. The tour leaders basically rounded up the San and offered them money to perform for the tourist group at their own camp that night. They pitched up about quarter of a mile away and we all went over when it got dark. All the tourists were sat in a semi circle in camp chairs round the fire, with their drinks, having had a feast. It was all five star treatment. And the Galalabadimo San were ushered in as their entertainment.

It upset me at the time. It felt exploitative and disrespectful. But, you know, they got paid. As I would if I did a gig. This was something like a micro-clash of civilisations and ideologies. It's still an ugly image to me though.

I know my motives were purely music focused when I went out there. It was a passion for this music. Having disappeared off into the sunset with the recordings I'm grateful for this opportunity to give something back by way of donation of the recordings and of the income from this production to the

!Kwhwa ttu San Culture and Education Centre (khwattu.org).

I'm assured it's the most direct contribution I could make to support the community, lives and culture of these people I met but lost contact with.

Were you carrying all your money in your sock?

Yes! Pula, the Botswana notes are called Pula which translates as rain. Water is so valuable they named their cash after it!

Then you traveled to the Khutse Reserve? How did you meet the oil can guitar band?

That oil can guitar music on the Khutse tracks is pretty great sounding, can you tell us about the guitar?

I just came across this bunch of lads when we were passing through Khutse on the way back to the capital city Gaborone. It was a bigger settlement than Galalabadimo, more like a village. The oil can guitar was the first one I'd seen, they're pretty common now. They were basically mimicking music they'd heard on the radio, writing their own songs. One of them mentions Gaborone so I guess there was a yearning there for escaping the small town. Or maybe they were taking the piss out of the city folk. These lads noticeably had a lot more front than the young in Galalabadimo.

Where did this recording fall in relationship to your Merz project? Did it inspire any Merz music directly/ indirectly?

I recorded this a few years before I started the Merz thing in London. I made five separate trips to the continent of Africa over five years and spent time in 14 African countries, South, East, North and West. No doubt the music I soaked up there made an impression deep inside me. So when I started songwriting and arranging the tracks on Merz recordings, it had to come out in some fashion. It wasn't forced, but there was an African ingredient in there. I'm not claiming to be a fusion pioneer, but I hear a lot of the newer music made by younger generations in London now, no matter what race the musicians, and I can hear the significant influence of the African and Caribbean London communities in the music. They've grown up together, gone to the same schools, same clubs. It's also a spirit. Not just forms and sounds. That's harder to relate to people.

Was there a difference in your expectation vs what you came away with, thinking about the music?

I was surprised by how vocal-based Southern African rural music is. People commonly think of drumming and rhythm when they think of African music. In the South there's not many forests. There's a lot of bush and desert. West Africa, Central and East have a lot of forest so there's a ton of wood to build drums with. There are drums in the South but not as much poly rhythmic drumming traditions as there are elsewhere. There's a heavy Christian hymn influence in much of the singing in the South too. It's actually harder to find the really old, pre-Christian vocal songs. That's what you get with spectacular effect from the San.

30 years! You’re in the desert now, any full circle, retrospective thoughts?

I still love being in the desert! "It's clean" (Lawrence of Arabia). There's space here to be yourself and the dominant presence is the natural world, not materialism. So that has a greater sway on you, which is no doubt a healthy thing. I haven't had a TV or home wifi for two years, I feel more in touch with what's really going on. It's clear what should be ignored and what should be given due consideration. I'd warrant that the San have had similar, likely more profound perspectives while the world changed around them. I'm no anthropologist and I don't really know them, but I sensed a collective wisdom.

Your most recent release is a collaboration with musicians Laraaji and Shazad Ismaily, which was based on a residency you did in Bern, Switzerland where the music was developed into an experiential installation A Monastic Gig, in collaboration with desert based visual artist Jed Ochmanek. Can you tell us a little about that residency, your citation of Alice Coltrane, and the experience you were trying to create and then converting that into a record and a digital release?

I was invited to be Associated Artist at the Dampfzentrale music and contemporary dance venue in Bern, Switzerland and had Carte Blanche to initiate projects. On a trip through Ojai, California, I stopped at a really peaceful outdoor cafe in the hills. No one was talking, a few people were reading books, it was so tranquil. I thought it'd be great to have 'A Monastic Cafe'; a normal cafe but patrons were required to be silent and not use electronic devices. Bliss. Then I thought you could hold 'A Monastic Gig' - same disciplines. On that road trip I also visited the Ashram of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda in the Agoura Hills, outside LA (they since sold the property and, sadly, it burnt down in the wildfires of 2018). I'm a devotee of Alice's music, particularly her harp and mono-synth stuff. That inspired me to invite Laraaji and Shahzad Ismaily to join me with their auto-harp and mono-synth respectively.

Laraaji performed with me at 'A Monastic Gig' which was held in this grand, ex-power station space. Jed Ochmanek who is an LA and Joshua Tree-based visual artist, designed the whole environment, including an hour and a quarter long film of his poured painting which was projected on a huge screen behind Laraaji and myself. The audience were asked to enter the room in silence, experience the concert in silence and leave in silence. They were sat all around us on austere wooden benches which were supposed to encourage a humble posture, but as a side-effect caused a few complaints.

In retrospect I find it even more interesting how an experience changes if you take speaking out of it. It's a surprisingly rare occasion that gives you that experience. And personally I feel there's no shortage of hot air, there's too much talk. What happens if you just zip it for a sec'.

That concert with Laraaji turned into an album, including recordings I'd made with Shahzad Ismaily, titled Dreams of Sleep and Wakes of Sound. All the instruments other than the Moog Rogue mono-synth are zithers, harps, santoor, guitar. It has a semi-serious genre of Industrial-Devotional, devotional music for a post-industrial age. It's a beautiful double vinyl record with artwork by Jed Ochmanek and Graphic design by the Swiss-based Maison Standard. On release it was selected as The Guardian newspaper's 'Contemporary Album of the Month'.

Laraaji : Merz : Ochmanek

A Monastic Gig, 2018